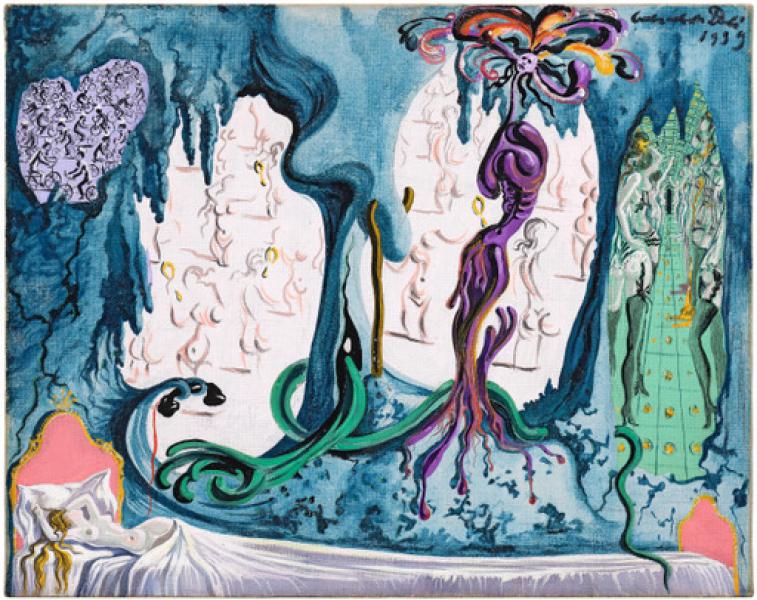

Le rêve de Vénus, 1939

Oil on canvas pasted on cardboard, signed and dated 1939 top right.

40.50 x 50.50 cm

Project for a living painting for the Dream of Venus pavilion for the World's Fair in New York, 1939

Provenance:

Former collection of Comte Alain Chenon de Leche, Paris, 1939

Sale, study of Me Tabutin & de Dianous, Marseille, March 11, 2000

Private collection, South of France

Exhibitions :

Salvador Dalí, Casino Communal de Knokke-le-Zoute, 1 July - 10 September 1956, under n°39.

Certificate established by Mr Nicolas Descharnes for the Descharnes Archives.

In June 1939, Dali imagined for the World's Fair in New York a surrealist work in the form of a whole pavilion, an ephemeral and interactive architecture, called The Dream of Venus.

On the baroque façade of the building, a Venus by Boticelli is enthroned alongside sculptures of mermaids, while a fish head served as the entrance window, topped by a pair of spread legs. Inside, visitors were immersed in a dreamlike world of installations including two pools that hosted a water show of nude naiads and a room in which Venus was watched sleeping.

Shortly before, an exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York (from March 21 to April 18, 1939) had been organized as a prelude to the great surrealist coup d'éclat that was the pavilion at the World's Fair, which was to make French surrealism better known across the Atlantic and which in fact constituted one of the first installations in the history of art.

Between popular fairground attraction, theater, architecture, painting and dance, the Dream of Venus Pavilion was intended to be a true immersive artistic experience.

The painting that we present, illustrating the room of Venus, testifies to the American adventure of Salvador Dali and the evolution of his practice towards a contemporary art such as it will be experimented after the war in the second part of the XXth century.

Coming from a private collection, it formerly belonged to Viscount Alain de Léché.

The "Declaration of independence of the imagination and the rights of the man to his own madness".

Salvador Dali's intervention in the World's Fair in New York in 1939 is an opportunity for the artist to assert loud and clear the independence of his status.

No judgment of any kind, should, according to him, be placed above the imaginative poetics of the artist, thus guaranteeing the independence of creation.

At the time when the committee of organization of the Fair prohibits him to erect outside the pavilion a body of woman to the head of fish, Dali, who does not decolour, makes print fliers to defend " the independence of the imagination and the rights of the man to his own madness ", defending a purely poetic and imaginative right as universal and fundamental.

He refers to Greek mythology, which did not refrain from creating women with fish tails and other men with bull heads.

"Any authentically original idea, presenting itself without 'known antecedents', is systematically rejected, watered down, mishandled, chewed up, vomited, destroyed, yes, and even "worse - reduced to the most monstrous of mediocrities. The excuse given is always the vulgarity of the vast majority of the public. I insist that this is absolutely false. The public is infinitely superior to the garbage that is served up daily. The masses have always known where to find true poetry. The misunderstanding has occurred entirely because of these 'intermediaries of culture' who, with their grand airs and superior songs, come between the creator and the public."

Dali then calls on American artists to propagate this claim.

This political intervention illustrates well the position that Dali intends to hold as an artist, at the same time in margin of the society, while infiltrating it, sometimes playing of its codes to better defy it.

The Dream of Venus Pavilion

If no plan of the Dream of Venus pavilion has survived, this ephemeral architecture realized by Dali for the World's Fair of New York in 1939, photographic reports and numerous descriptions illustrate it rather precisely, allowing us to reconstruct it.

One reached the interior of the pavilion by passing under two columns which constituted spread out female legs. A fish head placed between them served as an entrance window.

A giant aquarium whose walls represented a city in ruins, was furnished with various unusual objects such as a piano with a dummy forming a keyboard, a telephone handset in suspension... In the water, mermaids evolved half-naked.

One walked along this aquarium as if strolling in a dream.

Another set came next, a "dry zone", with motifs dear to Dali: soft watches, a burning giraffe, surrealist mannequins made of various objects... This long painted set is now preserved at the Hiroshima Prefectural Art Museum in Japan.

Next to the three-dimensional reconstruction of a painting by Magritte, the Venus bed was spread out on the floor, a bed 11 meters long.

A naked woman was lying on it, covered up to her chest. An image inspired by Giorgione's Sleeping Venus (1508-1510), a painting reworked by Titian after his death.

In the background, a mirror. On the ceiling, open umbrellas.

Next to the bed, a young woman put her finger over her mouth to ask the viewer to be silent as she passed the bed where Venus was sleeping.

The walk ended with an installation that Dali had already presented at the International Exhibition of Surrealism in Paris in 1938: a rainy cab, a real vehicle inside which the rain fell.

Sleeping Venus made us penetrate in her dream that we could go through at wolf's pace, provided not to wake her up. The spectator thus had a double position: seeing the sleeper dreaming, he also had access to the interior of his mind, to his subconscious and to his deep intimacy, thus intermingling dream and reality, confusing their essence.

The painting The Dream of Venus

The painting that we present is thus a preparatory work for the conception of this pavilion of Venus. Several images eminently surreal and familiar to the language of the artist are combined in this work.

The long bed first of all which appears to Dali since 1930 within the framework of the illustration of a collection of poetries of Rene Char, Artine, as to figure, by an unseen length, the quantity of dreams which follow one another during the sleep.

The cyclists then, haunting image, which could represent, according to the specialist of Dali, Nicolas Descharnes, the average bureaucrats. Those against whom he rises precisely in his pamphlet published to defend the rights to independence of the imagination. Wearing a stone on their heads, they go absurdly through life, conforming to imbecilic prescriptions that they try to enforce.

The naked female torsos getting ready, armed with face to hands, are a repeated motif in the background of the composition, replaced in the final installation by a mirror.

A chimera, a soft, rubbery structure, rises from a dripping cave background. A crutch and a telephone, hard objects dear to the artist, mingle with the soft structures that support them, in an inversion of values.

The corridor of Palladio is another characteristic element of the convocation of the unconscious, with its paving of drawers and this alignment of women offered in suspenders, a true corridor of brothel.

Undoubtedly this preparatory painting reveals ambitions for the construction of the Pavilion of Venus that Dali was unable to carry out for essentially financial reasons. Tensions were indeed very quickly felt between the artist and the main financier of the project, Mr. W. Gardner, obliging Dali to concessions, certainly denounced but for as much undergone within the framework of the creation of this project, where the surrealist excess of the artist inevitably came up against more grounded considerations.